The disease begins like many others. Fatigue. Muscle soreness. Fever. Loss of appetite. Sore throat.

Videos by TravelAwaits

You might easily think you’d come down with the flu. A hot bath, lots of fluids, and a few days of rest should be enough to set you right.

But instead of improving, your condition deteriorates. Chest pains. Labored breathing. Headache. Disorientation. Vomiting. Rash.

And, in the worst cases, bleeding. Coughing up blood. Vomiting blood. Bleeding into the eyes. Internal bleeding. It just won’t clot. Eventually, you slip into a coma and die from blood loss.

This is the terrible fate that awaits anywhere from 25-90% of those infected with the ebola virus.

The mere mention of ebola causes many of us to reflect on the horrifying outbreak that plagued the West African nations of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone from 2013 to 2016, leading to over 26,000 cases, of which 11,310 were fatal. There were also sufferers in Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, Spain, Italy, the UK, and even the United States, where one person died.

But it would be a mistake to think about ebola in the past tense. It has returned yet again, this time in the Equateur province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Since early April of this year, there have been 30 suspected cases, with 18 reported dead.

Where does ebola come from? What can be done to stop it from spreading? What does this mean for travelers? Will there ever be a vaccine?

We’ll get to those questions. But first and foremost, it’s important to remember that ebola tends to originate among some of the most vulnerable populations on Earth. If you have a few bucks to spare, consider donating to these UN organizations that fight back against infectious disease.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Vardion/Wikimedia

How It Spreads

Ebola was first documented in 1976. The virus and associated disease appeared in two different places nearly simultaneously: in Nzara in what is now South Sudan, and in Yambuku in what is now the DRC. The virus was named for the Ebola River, which is proximate to the site of the first Congolese cases. (The Nzara cases were only later identified as ebola after the same disease appeared in Congo some months later.)

That initial outbreak in the DRC was one of the most deadly per capita in history. The mystery illness killed 218 of 318 victims, corresponding to a 68% death rate. (In Sudan, 151 of 284 patients died — 53%.)

Since 1976, there have been at least 26 additional outbreaks, of which the infamous 2013-16 panic was by far the most lethal. Apart from the countries mentioned, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire, South Africa, and Uganda have also struggled with ebola.

There are five known viruses in the ebola genus, four of which cause disease in humans. The most dangerous is the strain known as Zaire ebolavirus (the DRC was formerly known as ‘Zaire’). This strain was the one responsible for that 2013-16 West African contagion.

The principal carrier seems to be the fruit bat, although other animals (monkeys, gorillas, chimpanzees, antelopes, porcupines) may also serve as vectors. It is not known precisely how the virus makes the leap from wild animals to humans, but direct contact is presumably required; mercifully, ebola is not known to be airborne.

Between humans, ebola spreads easily via bodily fluids or surfaces contaminated with infected bodily fluids. Since the symptoms of infection may take as many as 20 days to manifest, and humans remain contagious as long as the virus is in their body, it’s not hard to see how ebola can quickly work its way through a population.

It is noteworthy that ebola tends to pop up in market or border towns where many people come and go.

A fruit bat.

Prevention and Treatment

Alas, there’s precious little to be said about preventing ebola. Mostly, it boils down to common sense: don’t have unprotected sex with strangers; avoid blood, vomit, and other bodily fluids; stay out of areas where there are ongoing outbreaks.

Of course, in reality, disease spreads because contagious individuals are not always symptomatic. And even if they are, nobody assumes that a friend with a fever may in fact have ebola. Plus it doesn’t necessarily take much contact to spread the disease; even doctors and nurses moderately exposed to infected individuals have been known to take ill.

There is no medication known to ‘cure’ ebola, though research continues. Treatment instead focuses on supporting the body as it fights off the virus. (Being a virus and not a bacterium, ebola is invulnerable to antibiotics.)

In particular, healthcare providers focus on quarantining infected or potentially infected persons, keeping them hydrated, maintaining electrolytic balance, and preventing renal failure. Since ebola typically weakens blood clotting, patients also often require red blood cells, platelets, and plasma.

An experimental vaccine called rVSV-ZEBOV has been reported to have 70-100% effectiveness in preventing the spread of ebola. It was deployed on an emergency basis in Guinea in 2016, and again in the DRC in 2017. As of this writing, it is being administered to combat the ongoing outbreak.

However, some scholars have questions the reliability of the data.

It may be true that most of those who were given the vaccine did not ultimately contract ebola, but there was no unvaccinated control group to compare them against. (Nor could there be. It would be pretty unethical to decline vaccinating part of a vulnerable population simply for the sake of an experiment.)

Vaccine rVSV-ZEBOV is not commercially available, and its efficacy remains a matter of debate. But there is at least some hope that an ebola vaccine may be on the horizon.

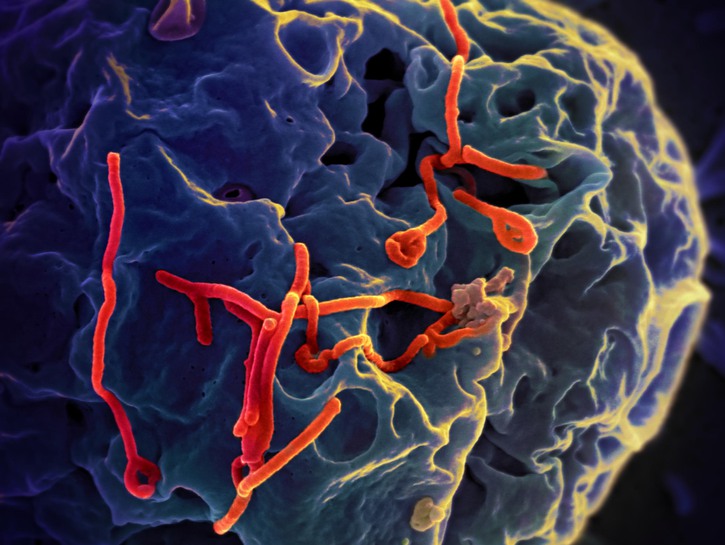

Ebola viruses under microscope. NIAID/Flickr

How does this affect travelers?

The current outbreak has been relatively isolated and is confined to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. If it can be contained, it should pose very little risk to travelers.

Unfortunately, despite its natural wealth and beauty, the DRC is not a place most tourists would be inclined to visit. It has been wracked by resource wars, internal instability, terrorism, and kleptocracy for decades, all of which have left it as one of the poorest and most dangerous countries to visit on the continent. Even before ebola again reared its ugly head, the US State Department was encouraging Americans to reconsider traveling there.

It’s worth knowing something about the vectors, risk factors, and symptoms of ebola if you’re planning to visit or volunteer in West or Sub-Saharan Africa, since we’ve seen the virus recur time and again. Because the disease can spread rapidly, it’s best to be prepared for all contingencies.

On the other hand, the World Health Organization is working with the DRC Health Ministry to minimize the damage, and you can rest assured they’re taking this very seriously.

One final piece of advice for those visiting West or Central Africa: don’t eat so-called ‘bushmeat.’ Bushmeat is the flesh of wild animals hunted in the Sub-Saharan jungles. It’s quite common in rural areas and often treated as a delicacy in urban centers.

As much as we like to be open to other cultures’ rarities, this is one you should give a miss. Not only is it a threat to the biodiversity of the jungle, but the consumption of bushmeat may well be one of the ways ebola spreads from animals to humans. While sufficient heat will kill the ebola virus, undercooked bushmeat could easily be contaminated.